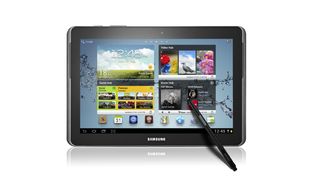

The future of touch control, the S Pen and the Note II

Pro graphic design S Pen input on your smartphone

Touch technology, it all started with the humble button, and now there's a revolution in the world of touch input every few years.

Take the Samsung GALAXY Note II for example; it manages to couple its S Pen with 1024 levels of pressure sensitivity. That means professional graphic design tablet style pen input, on a phone!

With Samsung already going beyond touch in its GALAXY S4, using sensors to create Minority Report style gesture interaction, it really does beg the question - is there anywhere left for touch to go and what's the future of touch control?

Before we look to the future though, it's worth going back in time.

Touching on the past

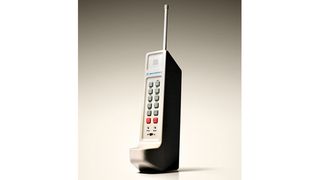

Switches, Buttons, jog-wheels. When mobile phones first hit our hands, it wasn't a touchscreen we were touching, but clickable, physical buttons. The Motorola Dynatac for example - also known as the "Saved by the Bell" Zack Morris phone! - had plenty of buttons and, in its original form, no screen to speak of.

Things moved on from physical buttons to touchscreen though, with the IBM Simon in 1993, the first touch phone and, according to most, the very first smartphone. These early touchscreens weren't what we've come to know on modern day smartphones though; instead they used something called resistive technology.

Resistive screens require pressure when interacting with them – you have to press, and, sometimes, press pretty hard to register an action. Phones and devices with resistive screens generally came bundled with a stylus – a small, usually plastic pen device.

Get the best Black Friday deals direct to your inbox, plus news, reviews, and more.

Sign up to be the first to know about unmissable Black Friday deals on top tech, plus get all your favorite TechRadar content.

Why? Because it isn't particularly comfortable swiping on a resistive screen with a finger as pressure needs to be applied throughout the swipe. Plus, given the fact resistive screens have to bend slightly, glass also can't be used, so manufacturers had to make do with plastic. While these early examples of the tech were called touchscreens, they weren't much fun to touch, with the plastic scratching easily and not feeling rich.

It's therefore little wonder that capacitive screens took off.

Capacitive screens use the body's electric conducting properties to acknowledge a finger press. To the uninitiated this may sound like science fiction, but it results in an ultimately comfortable touch screen experience – and on glass no less.

A Note on the Present

With capacitive touchscreens arriving on phones such as the Samsung i8910, the first phone capable of capturing 720p video, right through to the Samsung GALAXY range, they were clearly the way to go in terms of user experience.

While pleasing 99% of users, capacitive touchscreens still fell behind resistive screens in one area and one area alone – precision.

The finger isn't mightier than the pen in this respect. With resistive screens working with pressure, they were very, very precise when used with a pointed object like a stylus.

Capacitive screens, in contrast, wouldn't work with pen input. Why? Because they require a distortion in the screen's electrostatic field. A finger can do this, but as plastic doesn't conduct electricity, it can't.

It took some out-of-the-box thinking to take touch control to the next level, and with their original Samsung GALAXY Note, Samsung prevailed.

The GALAXY Note coupled a capacitive screen with a Wacom layer, called a digitizer. It recognised when the accompanying S Pen was touching the screen with pixel-precision, making for an unprecedented pen-input experience on a mobile touch device.

In the Samsung GALAXY Note II, Note 10.1 and new Note 8.0, we can now experience the zenith of touch input to date. With an incredible 1024 levels of pressure sensitivity, Samsung has blossomed its relationship with Wacom to produce an incredible, err, fruit.

Bizarre fruit analogies aside, the result is a truly complete pen-input experience that comes considerably closer to pen and paper than ever before, with the many advantages of being digital.

Most Popular